Once part of the traditional homelands of Northern California’s indigenous peoples, the region’s national parks, monuments, and recreation areas both preserve native lands and are reminders of the impacts of colonization and settlement. While national park service facilities allow visitors to experience a semblance of the natural world that the state’s Native Americans revered, for tribal members the parks can also symbolize the disruption of their ancestors’ traditional way of life.

In recent years, there’s been a growing awareness of the gap between the highest ideals of the national parks and their impacts on Native American tribes. Increasingly, tribal members are working with the park service both on environmental initiatives and on more inclusive presentations of how the stories of individual parks and monuments are conveyed to the public. And in a major historic change, both Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland and Park Service Director Chuck Sams are members of indigenous tribes—the first Native Americans to serve in these roles.

Listed from north to south, here’s a look at California’s national parks and monuments with strong ties to the state’s indigenous peoples.

Lava Beds National Monument

About a 90-mile drive northwest of Mt. Shasta in the traditional territory of the Modoc people, Lava Beds National Monument is home to one of California’s most extensive areas of rock art.

Some of the thousands of petroglyphs were created 6,000 years ago, while the monument’s pictographs were painted as far back as 1,500 years. Most of the rock art at Lava Beds is abstract and geometric, and experts believe both the pictograph and petroglyph styles at Lava Beds were unique to the area.

The best place to see rock art in Lava Beds is at the aptly named Petroglyph Point, once on an island in Tule Lake, which was drained for grazing and farming in the early 1900s. A short interpretive trail explores the cliff, which, with its 5,000 petroglyphs, has one of North America’s highest rock art concentrations.

Redwood National and State Parks

While the Yurok and Tolowa people used logs from fallen redwoods for dwellings and dugout canoes, these trees were seen as something far more important than just an available building material. Redwoods—the tallest trees in the world—were regarded as sacred beings.

The Yurok and Tolowa remain a part of these magnificent forests, which are protected as part of the Redwood and State National Parks in Del Norte and Humboldt counties. Tribal members still present dance demonstrations at the park, including the Tolowa’s Needash (also spelled Nee-Dash and Ne’Dosh), a renewal ceremony. And the Yurok have taken the lead in a project with the National Park Service and other agencies to reintroduce endangered California condors into the park. The bird’s return is believed to signal the restoration of a spiritual balance.

Lassen Volcanic National Park

Long before the arrival of Europeans, the Achumawi, Atsugewi, Mountain Maidu, and Yahi/Yana peoples lived in the northeast California area now encompassed by Lassen Volcanic National Park. The Lassen region was a meeting place for the four indigenous groups and the archaeological record reveals evidence of human activity here at least as far back as 7,500 years ago.

During summer, the four tribes gathered foods at higher elevations before returning to their villages at lower elevations with the arrival of winter. The descendants of these original inhabitants still live nearby and consider the entire park a sacred place, particularly 10,457-foot Lassen Peak, which holds a special spiritual significance.

Tribal members have a long history of collaborating with the park service to tell the story of their people. Starting in the 1950s, Selena LaMarr, the park’s first woman naturalist and a member of the Atsugewi tribe, conducted demonstrations of traditional lifeways, such as basket weaving and acorn pounding. Tribal members continue to work with the park by helping to document and identify artifacts, such as those displayed at the historic Loomis Museum.

To learn more about the native cultures of the park, stop into the Kohm Yah-mah-nee Visitor Center. In the Mountain Maidu language, the name means “Snow Mountain,” and this was Lassen’s first facility to be named in a tribal language.

Point Reyes National Seashore

The Coast Miwok’s 10,000-year history at Point Reyes National Seashore north of San Francisco may have been disrupted but never broken, as evidenced by the continued presence in west Marin County of the Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria, a federation of Coast Miwok and Southern Pomo groups. Once home to scattered villages with as many as several hundred residents, Point Reyes is filled with archaeological sites related to the Coast Miwok. Although displaced from their homelands along this coastline and Tomales Bay, many Coast Miwok still live nearby and feel deep ties to Point Reyes. Theresa Harlan, the adopted daughter of a Coast Miwok couple, is fighting to preserve the 19th-century wood-frame home where at least four generations of her ancestors lived at the bay’s Felix Cove before the last of the family was evicted in 1956.

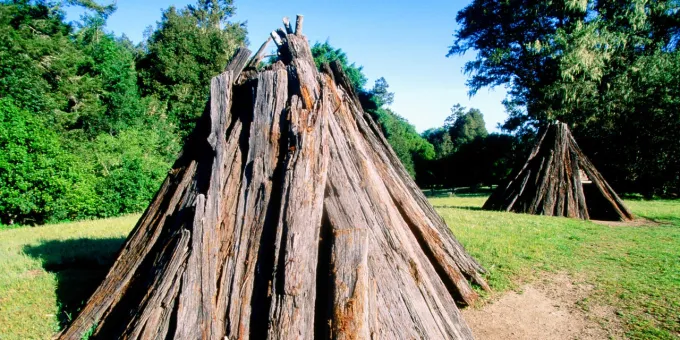

Near the Bear Valley Visitor Center, you can visit Kule Loklo, the re-creation of a Coast Miwok village with a roundhouse and other structures built using traditional materials. The Big Time Festival, a July cultural celebration with storytelling and traditional dances, has been held at Kule Loklo for many years, and the Miwok Archaeological Preserve of Marin conducts its California Indian Skills classes at the site.

Alcatraz Island, Golden Gate National Recreation Area

The San Francisco Bay Area’s Golden Gate National Recreation Area spreads across the ancestral lands of Northern California’s 14 Coast Miwok and 50 Ohlone tribes.

Among the most significant of the recreation area’s historic places is the Ohlone-Portolá Heritage Site, where Ohlone tribespeople led Gaspar de Portolá and his expedition to the top of Sweeny Ridge, giving the Spanish captain his first view of San Francisco Bay.

But the recreation area’s Native American history is not limited to the distant past, especially at Alcatraz Island, the location of an allegedly inescapable federal penitentiary nicknamed “The Rock.” In the 19th century Indians fighting the U.S. government, including during Northern California’s Modoc Wars, were imprisoned here. Then, in 1969, Alcatraz was the site of a 19-month occupation by Red Power activists when a group of about 100 indigenous protesters took over the island. They claimed Alcatraz as ancestral Indian land and sought to establish a Native American cultural center and university on the island. The occupation was considered a major landmark for the Native American political movement and an exhibit at the island commemorates the protest.

Yosemite National Park

The word ahwahnee was the original Native American name for Yosemite Valley and meant “the place of a gaping mouth.” The word is now most associated with Yosemite National Park’s landmark hotel The Ahwahnee. With The Ahwahnee’s many Native American–inspired design and architectural details, the hotel celebrates indigenous cultures, even though Yosemite’s own tribal peoples suffered greatly as they were displaced from their lands.

According to the National Park Service, seven of today’s Native American tribes and groups have ancestral connections to Yosemite, including the Southern Sierra Miwuk Nation. The Miwok (also spelled Me-Wuk and Miwuk) lived in the Yosemite region for almost 4,000 years before the beginning of the California Gold Rush and the establishment of the park. According to the park service, “thousands of Miwok people were killed or died of starvation” as they increasingly came into conflict with miners and militias. By the time the park was established, Yosemite’s native heritage became an exotic tourist attraction that included an Indian village and celebrations with insensitive, stereotyped depictions of indigenous life.

These days the park avoids a romanticized presentation of its past and takes a more accurate and inclusive look at the experience of Yosemite’s native people. Former Yosemite superintendent Michael Reynolds said “I, along with many, often struggle to find a better and more complete understanding of the difficulties that our people have caused to the lives and cultures of the native peoples of this land.”

At the Yosemite Museum, you can discover the history of the region’s Miwok and Paiute people and see demonstrations of basket weaving and other native crafts. Behind the museum, self-guided tours lead through the re-creation of the Indian Village of Ahwahnee, which has such traditional structures as bark-covered homes, a sweathouse, and a ceremonial roundhouse that’s still used for ceremonies by the local indigenous community.